Introduction¶

In 2025, a total of 16 flaky tests were addressed in the cortex codebase. In most cases, the flaky tests were fixed by code changes to either test or non-test code while keeping the test in place. In a few cases, the flaky tests were disabled. This document is an analysis of the 16 tests addressed: their causes, locations, and usefulness as indicators of real problems.

Most flaky tests analyzed were caused by race conditions in test code or incorrect assumptions about map iteration order in Go. The tests exposed problems in non-test code about as often as they didn't, indicating that flaky test failures should continue to be investigated.

Takeaways for test writers¶

Based on the analysis of tests addressed in Cortex in 2025, here is a short list of lessons applicable to many Go projects that, if kept in mind, would likely allow one to avoid some flaky tests:

- Map iteration order in Go is undefined. It can change from one execution to the next: ref

- If multiple communications can continue in a single

selectstatement (e.g. multiple channels have messages in them), one of them is picked pseudo-randomly: ref - Use synchronous operations in tests if available, or explicitly wait for asynchronous operations to complete.

- Be careful with floating point comparisons. Besides the typical advice of comparing with allowance for small differences, see also strconv.ParseFloat() and strconv.FormatFloat() for an idea of issues that might occur when floating point numbers are serialized.

Background¶

A flaky test is an automated test that, with no changes made to the test code or the code under test, passes on some invocations but fails on others. Flaky tests slow down progress and waste CI and human time. I am studying them in hopes to improve the experience of cortex project contributors.

For background, Cortex is a distributed time-series database written in Go, based on the Prometheus data model. It is generally used for monitoring web services and server compute infrastructure. Cortex ingests metrics, can perform a variety of mathematic operations on those metrics, and exposes additional HTTP APIs for managing various functions. It is unnecessary to know the details of Cortex to understand the analysis below. The most important thing to know is that Cortex is highly concurrent (even within individual processes in the distributed system).

Causes of flaky tests¶

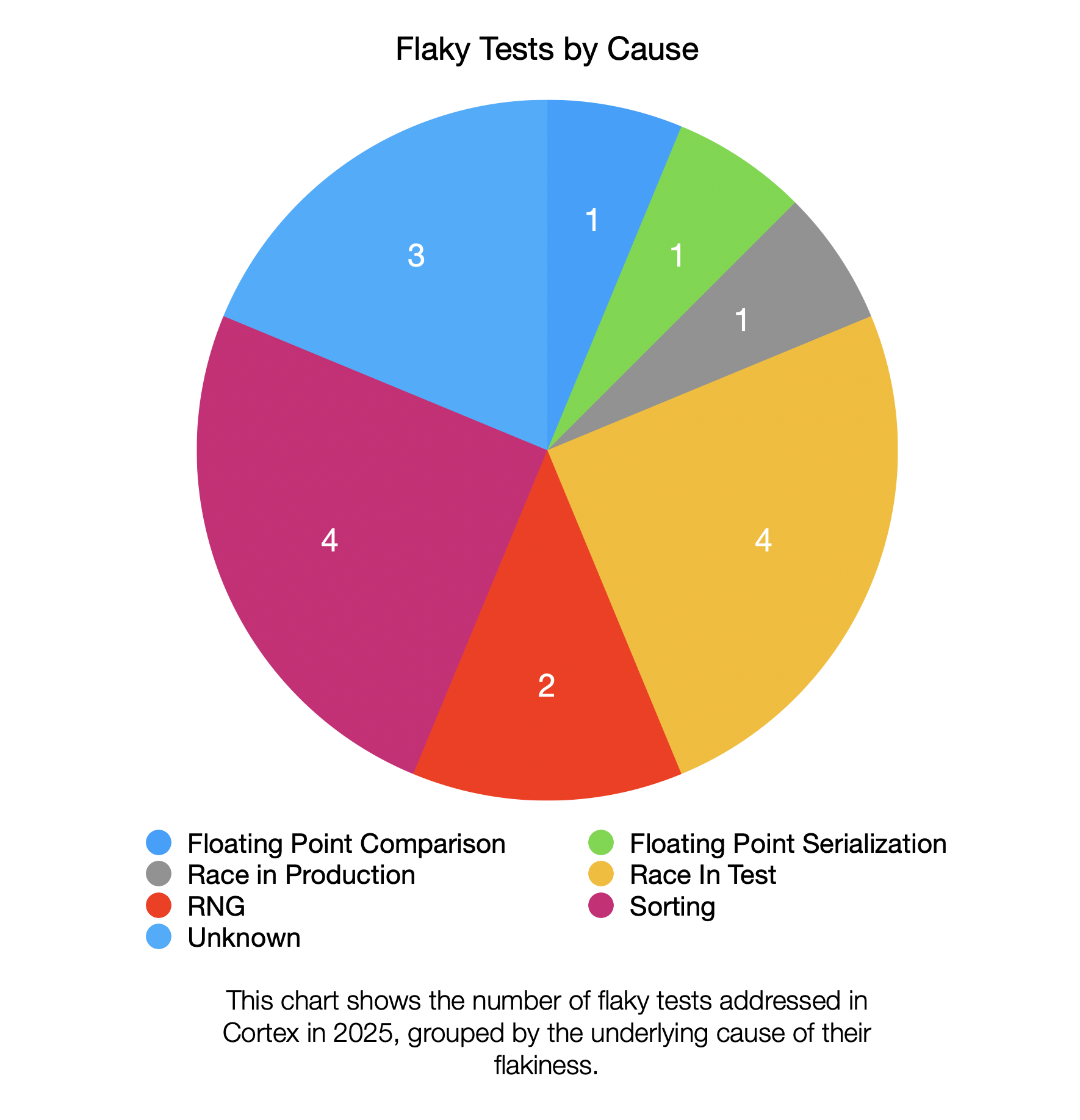

Of the 16 tests addressed in 2025, the underlying cause of the flaky behavior can be broken down into several categories:

The meaning of each cause is given below:

- Race in Test: A race condition in the test code/harness caused intermittent failures.

- Race in Production: A race condition in non-test code caused flaky behavior. This also means the race may be happening in production.

- Sorting: Some test cases assumed that sorting occurred when it didn't, leading to intermittent failures.

- RNG: Some tests failed intermittently due to randomness from random number generators. Generally speaking, with enough iterations using an RNG, a test might eventually uncover an edge case not properly handled by the code. Randomness might be used to choose between multiple available options. When code depends on which one is chosen first, unpredictable behavior can ensue.

- Floating Point Comparison: Exact equality checks between floating point numbers caused intermittent test failures even when the difference between the numbers was small enough to be acceptable. The failures were flaky because they occurred in fuzz tests where different numbers are compared in each iteration of the test.

- Floating Point (De)Serialization: Floating point serialization and deserialization introduced precision issues, causing comparisons to fail. The failures were flaky because they occurred in fuzz tests where different numbers are compared in each iteration of the test.

- Unknown: The test was disabled and investigation of the underlying cause is incomplete.

In the set of tests analyzed, the most common causes of flakiness (making up a combined total of 50% of the flaky tests) were race conditions in test code and sorting problems.

Race conditions in test code¶

What do race conditions in test code look like? Sometimes they are easy to spot and fix, like this one:

func TestSchedulerShutdown_FrontendLoop(t *testing.T) {

scheduler, frontendClient, _ := setupScheduler(t, nil)

frontendLoop := initFrontendLoop(t, frontendClient, "frontend-12345")

// Stop the scheduler. This will disable receiving new requests from frontends.

scheduler.StopAsync()

// We can still send request to scheduler, but we get shutdown error back.

require.NoError(t, frontendLoop.Send(&schedulerpb.FrontendToScheduler{

Type: schedulerpb.ENQUEUE,

QueryID: 1,

UserID: "test",

HttpRequest: &httpgrpc.HTTPRequest{Method: "GET", Url: "/hello"},

}))

msg, err := frontendLoop.Recv()

require.NoError(t, err)

require.True(t, msg.Status == schedulerpb.SHUTTING_DOWN)

}

In the above test, an async shutdown operation was started. The test immediately continued, clearly under the assumption that the shutdown should have completed (see the final check). Sometimes the shutdown completed before the final check; sometimes it didn't. The fix was to make the main test goroutine block until the shutdown operation completed.

Note: This is a case where having both synchronous and asynchronous versions of an operation might be useful.

Sometimes race conditions in tests can be harder to spot, such as this one:

func TestMockKV_Watch(t *testing.T) {

// setupWatchTest spawns a goroutine to watch for events matching a particular key

// emitted by a mockKV. Any observed events are sent to callers via the returned channel.

// The goroutine can be stopped using the return cancel function and waited for using the

// returned wait group.

setupWatchTest := func(key string, prefix bool) (*mockKV, context.CancelFunc, chan *clientv3.Event, *sync.WaitGroup) {

kv := newMockKV()

// Use a condition to make sure the goroutine has started using the watch before

// we do anything to the mockKV that would emit an event the watcher is expecting

cond := sync.NewCond(&sync.Mutex{})

wg := sync.WaitGroup{}

ch := make(chan *clientv3.Event)

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

var ops []clientv3.OpOption

if prefix {

ops = []clientv3.OpOption{clientv3.WithPrefix()}

}

watch := kv.Watch(ctx, key, ops...)

cond.Broadcast()

for e := range watch {

if len(e.Events) > 0 {

ch <- e.Events[0]

}

}

}()

// Wait for the watcher goroutine to start actually watching

cond.L.Lock()

cond.Wait()

cond.L.Unlock()

return kv, cancel, ch, &wg

}

t.Run("watch stopped by context", func(t *testing.T) {

// Ensure we can use the cancel method of the context given to the watch

// to stop the watch

_, cancel, _, wg := setupWatchTest("/bar", false)

cancel()

wg.Wait()

})

...

This example comes from a mock key-value database client in Cortex. The test harness shown above starts a goroutine to watch for events on a channel, sending them to another channel where assertions will be made on them.

The problem is that cond.Wait() is effectively blocking until cond.Broadcast() is called but depending on execution order of the goroutines, that might happen before the main test goroutine reaches the cond.Wait() call. If that happens, cond.Wait() blocks indefinitely because there was only one call to Broadcast() that could unblock it but it already happened, so the test deadlocks.

This issue was solved by replacing sync.Cond with an additional sync.WaitGroup and the appropriate calls to Done() and Wait().

Sorting problems¶

Sorting was the cause of 4 flaky tests in this review. The issue at the root of all 4 tests was code that assumed golang map iteration order is consistent. It is not:

The iteration order over maps is not specified and is not guaranteed to be the same from one iteration to the next. https://go.dev/ref/spec#RangeClause

Here is an example from the test set:

childFragmentIDs := make(map[uint64]bool)

children := (*current).Children()

...

childIDs := make([]uint64, 0, len(childFragmentIDs))

for fragmentID := range childFragmentIDs {

childIDs = append(childIDs, fragmentID)

}

...

The order of childIDs is undefined. Assuming that the order of this slice is irrelevant, comparisons made in tests must ignore order, otherwise they will fail intermittently.

A more sinister version of the same problem can be seen in this example:

func (t *DiscardedSeriesTracker) UpdateMetrics() {

usersToDelete := make([]string, 0)

t.RLock()

for reason, userCounter := range t.reasonUserMap {

userCounter.RLock()

for user, seriesCounter := range userCounter.userSeriesMap {

seriesCounter.Lock()

count := len(seriesCounter.seriesCountMap)

t.discardedSeriesGauge.WithLabelValues(reason, user).Set(float64(count))

clear(seriesCounter.seriesCountMap)

if count == 0 {

usersToDelete = append(usersToDelete, user)

}

seriesCounter.Unlock()

}

userCounter.RUnlock()

if len(usersToDelete) > 0 {

userCounter.Lock()

for _, user := range usersToDelete {

if _, ok := userCounter.userSeriesMap[user]; ok {

t.discardedSeriesGauge.DeleteLabelValues(reason, user)

delete(userCounter.userSeriesMap, user)

}

}

userCounter.Unlock()

}

}

t.RUnlock()

}

Depending on the order of reasons in the iteration of t.reasonUserMap, this code can delete data from users it shouldn't. To see how, imagine we have two reasons reason1 and reason2. On the first iteration say we pick reason1 (implicitly this is a random choice made by the go compiler/runtime). We decide that user123 needs to be deleted. Then the next iteration of the outer loop occurs, for reason2. Imagine we decide no users need to be deleted. Unfortunately, we still have user123 in the usersToDelete slice, so it will be deleted from the data associated with reason2.

Unlike the earlier example, where the solution was to explicitly ignore the order of the slice, the solution here is to properly scope the variable usersToDelete so it is re-initialized at the beginning of each iteration of the outer loop.

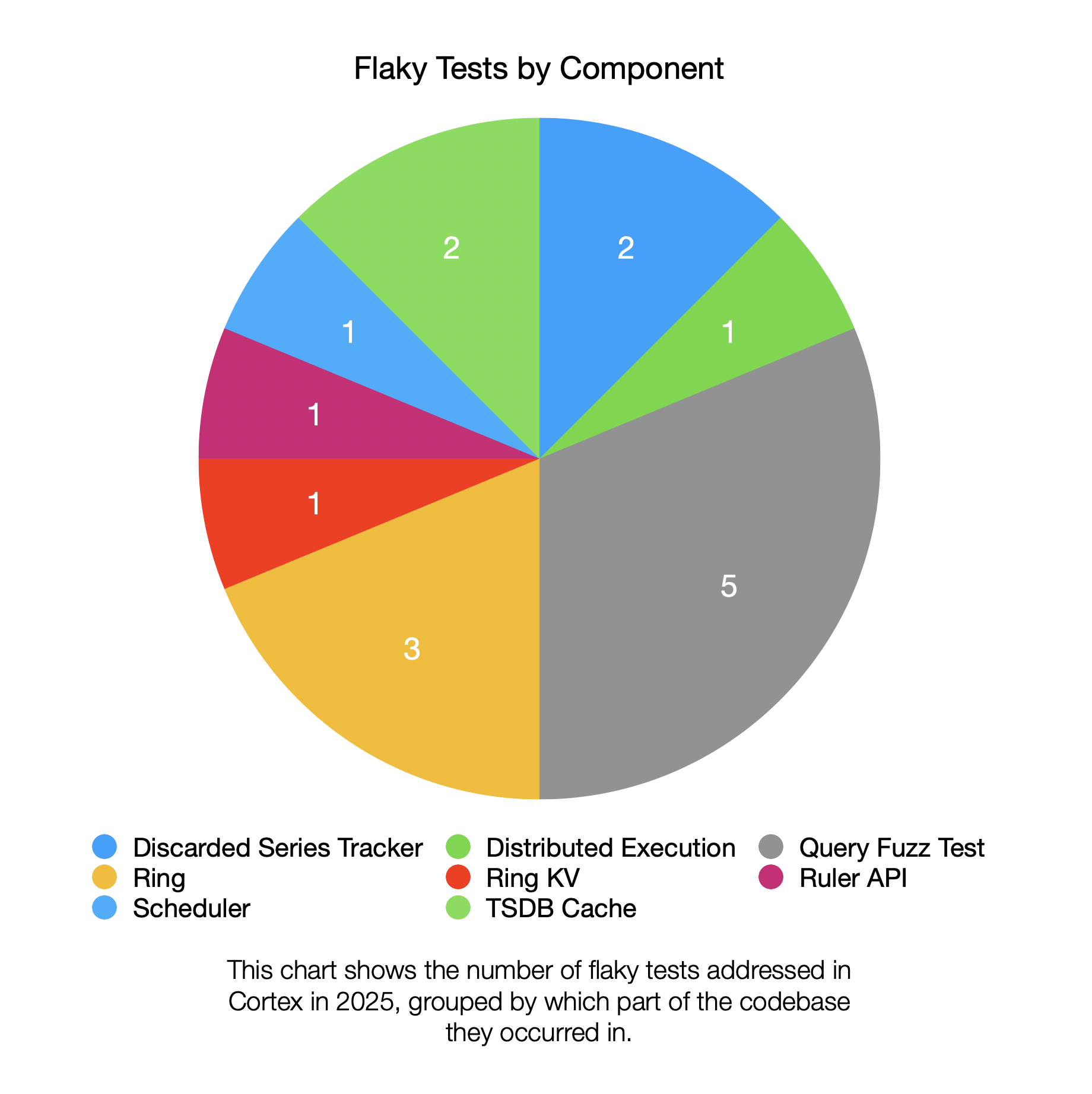

Locations of flaky tests¶

Flaky tests addressed in 2025 were spread across several parts of the codebase:

The biggest single component by number of flaky tests is the query fuzz tests (located here). Of the 5 flaky tests addressed in this area of the codebase, 2 involved floating point comparisons that were fixed by adjusting the comparison logic. The remaining 3 tests were disabled.

The 3 flaky tests in the ring package do not share any notable similarities with each other.

Usefulness of flaky tests¶

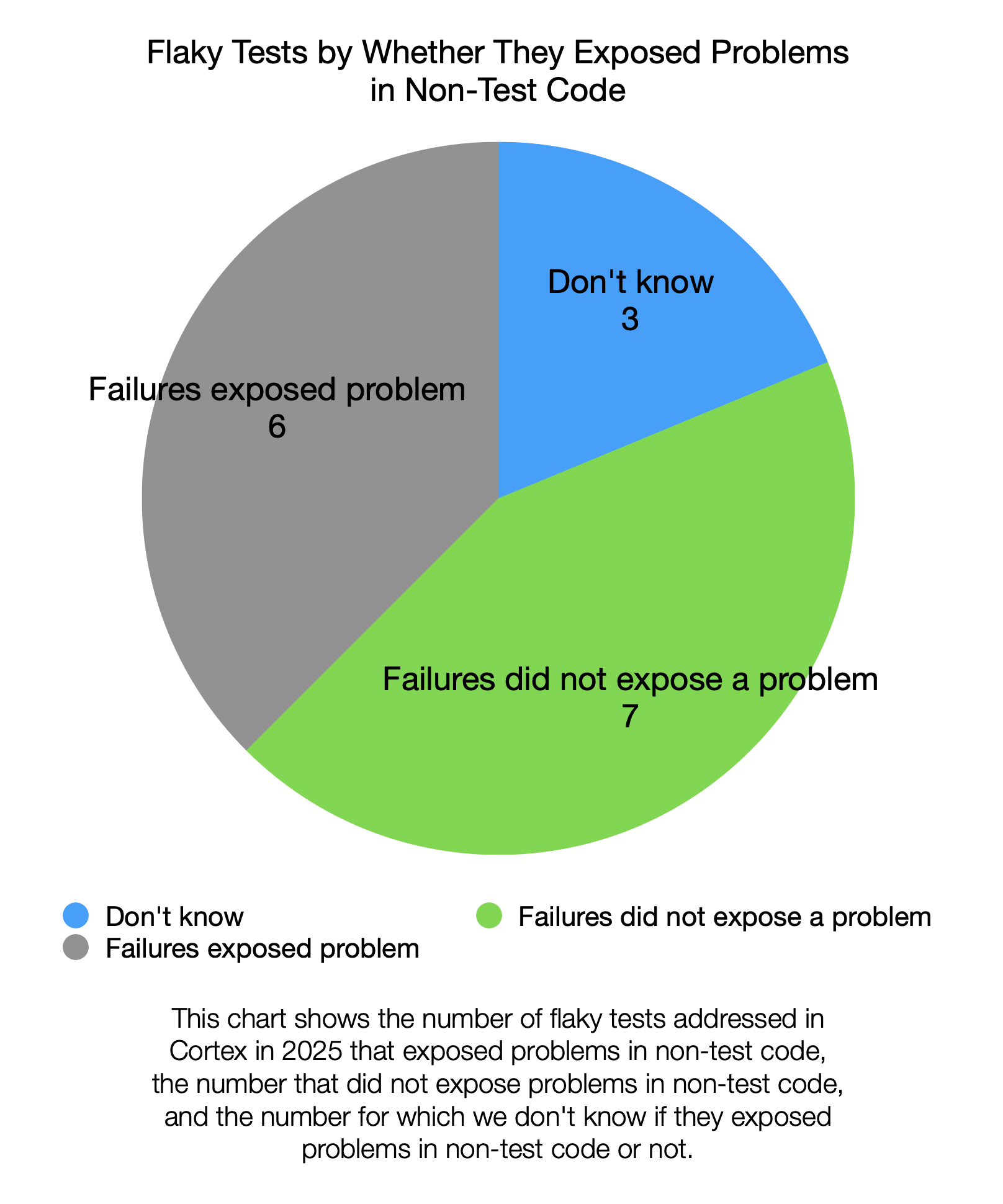

Of the 16 flaky tests addressed in 2025, many of them were caused by problems in test code. However, a similar number of tests exposed problems in non-test code: problems that could happen in production. A full breakdown is below:

From this, I tentatively conclude that flaky test failures should continue to be investigated instead of being disabled. They expose problems in non-test (i.e. production) code about as often as they don't.

The "Don't know" category represents the 3 fuzz tests that were disabled. Investigation of their cause of flakiness is incomplete.

Method¶

These are the steps I took to compile this report:

- Performed the following searches in GitHub and pulled the results into a spreadsheet

is:issue state:closed flaky closed:>=2025-01-01is:pr is:closed flaky closed:>=2025-01-01

- Deduplicated results from the two different searches

- Removed irrelevant issues and PRs (because they were closed without merging, were unrelated to flaky tests, etc.)

- Reviewed the code changes and discussions for each issue and recorded the following information for each one:

- Component where the issue occurred

- Cause of the flakiness

- Whether the fix involved changes to non-test code

- Whether the test failures exposed problems in non-test code (this was done as a second pass after "fix involved changes to non-test code" and was mainly to double-check this facet from a slightly different point of view)

- A brief summary of the issue and the fix

- Used pivot tables to summarize the results

Limitations¶

What is not represented in this analysis? The above analysis only included the flaky tests that were addressed in 2025. There were likely quite a few more flaky tests that failed intermittently in CI and development machines that were not discussed here. As a result, the generalizations we can draw from this set of tests are limited.

Thank you!¶

Thanks to the following contributors who helped address flaky tests in cortex in 2025:

- Harry John (https://github.com/harry671003)

- Charlie Le (https://github.com/CharlieTLe)

- Daniel Sabsay (https://github.com/dsabsay)

- Sungjin Lee (https://github.com/SungJin1212)

- Justin Jung (https://github.com/justinjung04)

- Ben Ye (https://github.com/yeya24)